Q4 2022 – “How Will the Federal Reserve Ring in the New Year?”

Q4 2022 – “How Will the Federal Reserve Ring in the New Year?”

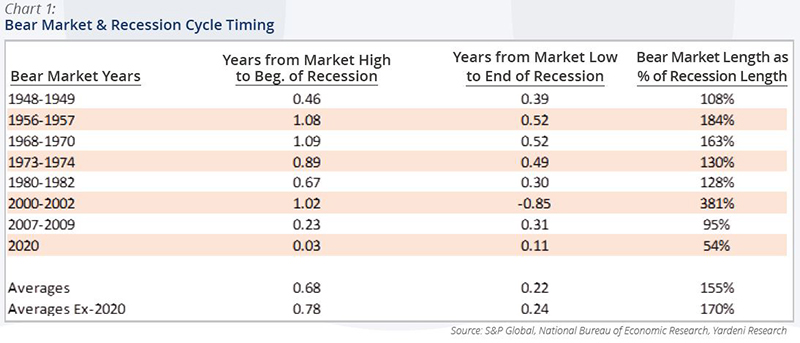

The U.S. equity market reversed some year-to-date losses in the 4th quarter but finished 2022 down for the full year. The S&P 500 Index was down 18.11% on a total return basis, the sixth worst calendar-year performance since 1926 and the worst since the 2008 recession (down 37%). The decline followed one of the best three-year runs in history, with annualized returns of just over 26% from 2019-2021; despite the recent weakness, the 4-year annualized return from 2019-2022 was 13.18%, above the long-term average annual index return of 12.01% from 1926-2022. The bond market provided only a modest “safe harbor” as the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Fixed Income Index was down 13.01% for the year.

The principal driver of negative performance for both markets was the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank’s (“the Fed”) numerous interest rate hikes during the year in a belated attempt to dampen demand and so quell inflation that was running at 40-year highs. After abandoning the notion that the pandemic-induced high inflation was merely transitory, and further prompted by the significant inflationary impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war, the Fed found itself in catch-up mode and increased the high-end of its overnight Federal Funds Rate target a total of seven times from 0.25% to 4.5%. The market currently expects at least two more Fed Funds hikes in early 2023 and a high of 5-5.25%. The Fed is also tightening monetary supply by allowing its balance sheet to decrease instead of buying securities to replace owned bonds as they mature. The Fed’s messaging is that it will do whatever is necessary to bring inflation closer to its 2% long-term target.

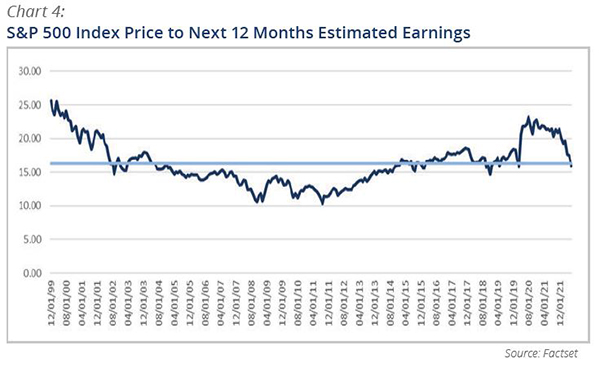

Higher interest rates, including higher short-term rates compared to longer-term rates (i.e., an inverted yield curve), portend weaker economic growth and a potential recession, as consumers’ and companies’ higher costs of funding purchases and investments crimps demand, lowers return on investments, and leaves fewer dollars for discretionary spending. Besides the threat of a recession that would weaken corporate earnings power, higher interest rates reduce the present value of expected future cash flows. This combination explains the harsh market reaction to the Fed’s actions to cool the economy and stifle inflation. The critical questions for investors going into 2023 are how much more tightening the Fed will do to control inflation, how effective those efforts will be, and how material the impact of higher rates will be on the economy and, by extension, corporate earnings.

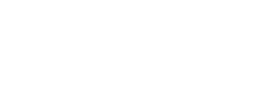

While the potentially weaker growth and related psychology have been quickly reflected in financial asset market prices, there is typically a lagged effect on actual economic performance from higher interest rates that is just now being revealed in the economic data. Given that 5 of the past 6 bear markets have been associated with recessions (the S&P 500 was down 19.8%, just short of a technical bear market, and bottomed during the recession of 1990), understanding the forces that may drive a hard (recession) or soft (low growth without a recession) economic landing is important.

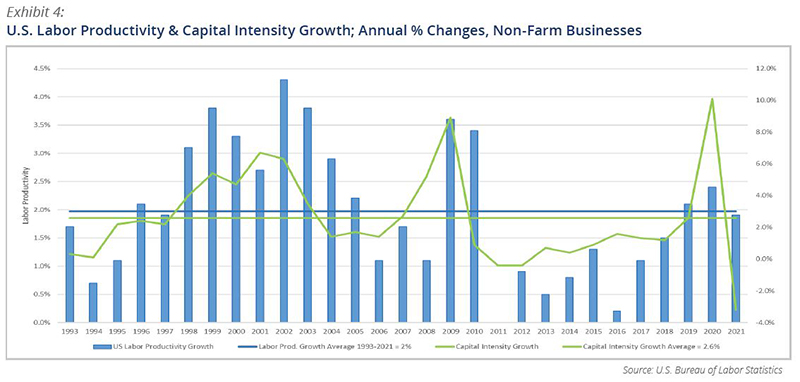

A review of the period from 1967-2022, shown in Exhibit 1, shows that the combination of abnormally high year-over-year inflation and low unemployment rates has been attendant to nearly every recession on record. The exception was the brief pandemic-induced recession of 2020, which was caused instead by an exogenous shock but precipitated the extraordinary monetary and fiscal response and subsequent economic reopening that has led to the present state of high inflation and low unemployment. Using history as a guide, the chart suggests a recession is more likely than not sometime in the coming months. The chart also shows that bear market lows, represented by the red vertical lines, have typically occurred during the technical recession period, suggesting that we could see new lows before a market recovery if we do slide into recession.

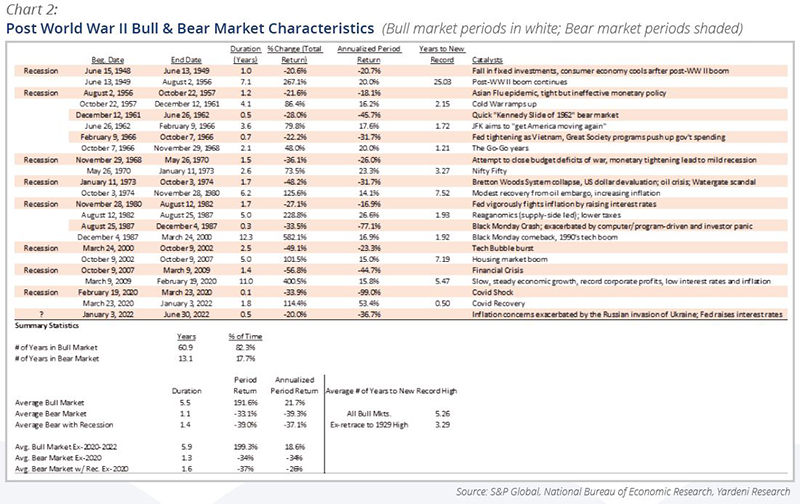

The causes of inflation have varied since the pandemic began. Initially, people sequestered themselves at home, increasing demand for upgraded housing that was particularly enabled by the emergency ultra-low interest rates adopted by the Fed and correspondingly low mortgage rates. Demand for goods became elevated compared to demand for services as people stayed home. Coupling the tremendous stimulus funds doled out by the government and the wealth effects of rising home and financial asset prices with supply chain challenges that increased the cost of manufacturing and delivering goods, available supply was lacking compared to demand and goods prices went up. As the economy reopened, demand for services returned. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exacerbated the inflation situation due to the sudden loss of supply of key commodity inputs such as oil and natural gas, wheat, and fertilizer that are produced there and which are net exports of those countries. The Fed’s (and most other world central banks’) tightening has begun to crimp demand and there are some signs of relief on the inflationary front, but it is not a uniform story.

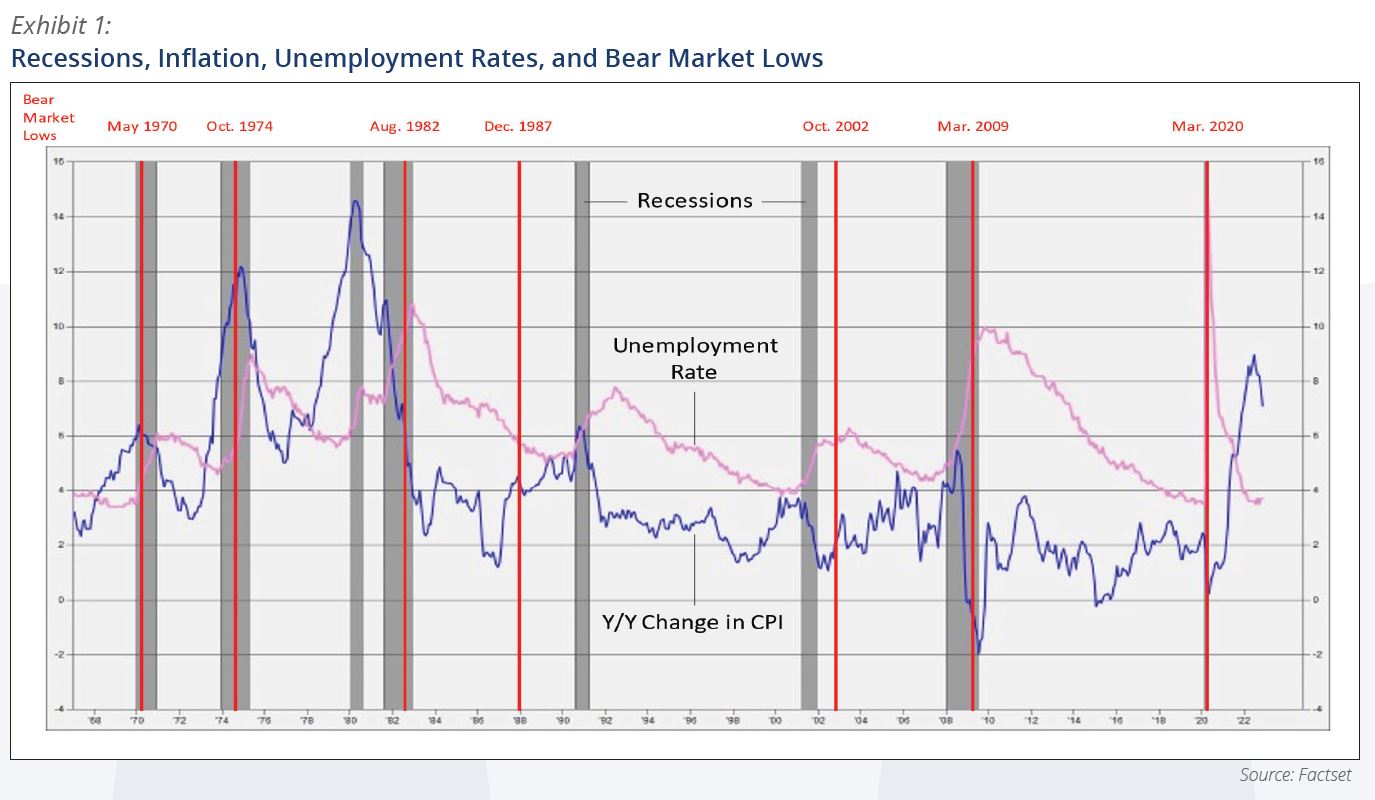

These trends are illustrated in Exhibit 2, which shows that year-over-year growth in overall U.S. inflation (the broadest blue line) has declined from a 9% high in June to a still historically high 7% in November. It also shows the spikes in energy and goods prices that drove overall CPI growth from 2021 through mid-2022 and the subsequent moderation in those categories in the second half of 2022.

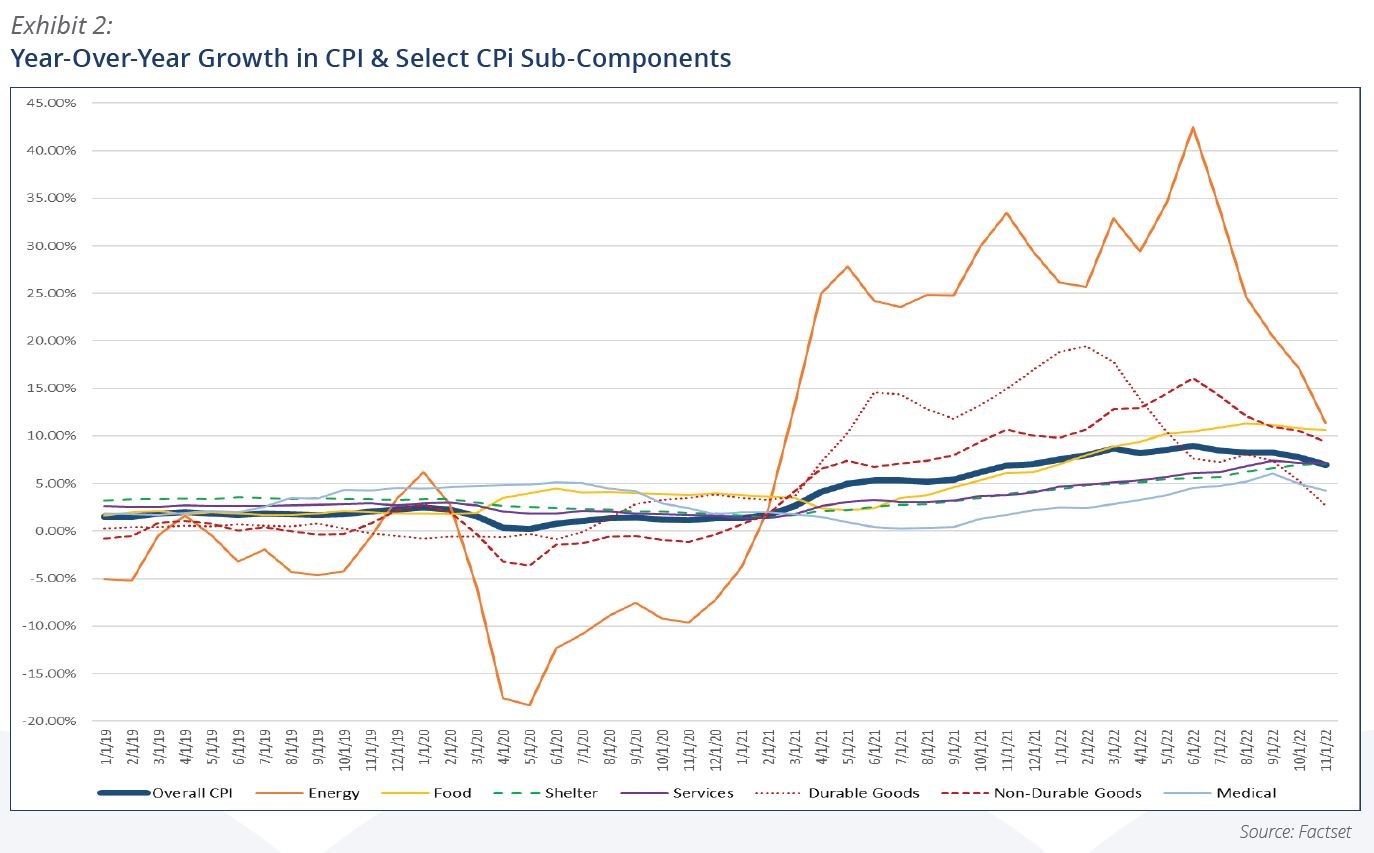

Exhibit 3 shows that higher interest rates have reduced demand, leading to a corresponding reduction in many economically sensitive commodity prices such as steel, aluminum, copper, and cardboard (in blue shades). The chart also shows the contrast with price trends for less discretionary items such as oil (in green) and food (in red shades), for which prices have held up better over the past year.

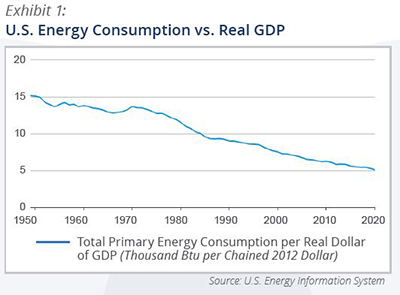

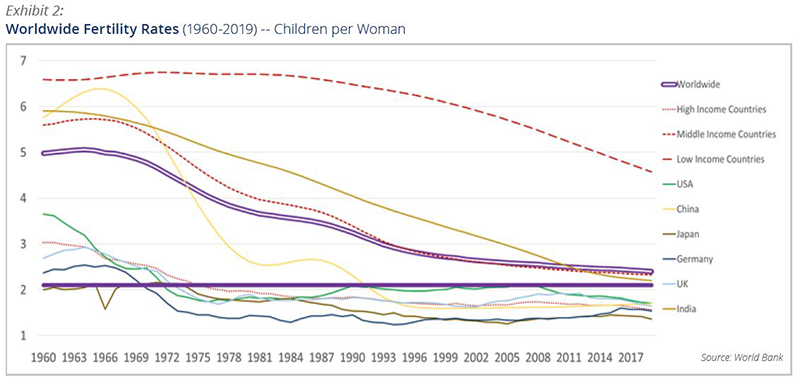

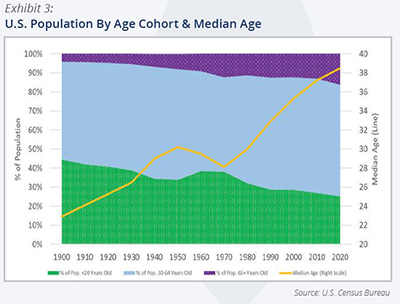

But wages and income are another key component of inflation given their impact on demand, and unemployment remains below 4%, close to 55-year lows, in part due to a low worker participation rate. Other factors, including retiring baby boomers, declining birth rate trends, and recently limited immigration also have and will contribute to keeping the labor market relatively tight. Though it has not fully kept up with overall inflation levels, year-over-year average hourly earnings in the U.S. has been robust, trending over 6% for most of the last 18 months. Though wage growth has decelerated since the March high of +6.75% (along with the more recent deceleration in overall CPI), the current level is still well above the 30-year average of +3.2%. Complicating the Fed’s inflation-fighting challenge is the fact that unlike commodity prices, wages tend to be stickier and are more difficult for companies to reverse; more typically, wages are reduced by culling employee rolls and resetting salary levels through eventual replacements. But for many industries that need specially trained workers or that have found it challenging to keep their businesses fully staffed or enable growth, that is not a viable option.

Higher consumer prices coupled with the tight labor market have emboldened workers in many industries to demand increased pay, including through threatened or actual strikes. For example, railroad industry workers last year received 24% pay raises that were retroactive to 2020; Delta Airlines recently offered pilots a 34% cumulative raise over three years that is likely to become a benchmark for other airlines; and New York City nurses just went on strike at multiple hospitals. There are other sources boosting income in the U.S., including an 8.7% increase in social security benefits for 2023 due to the legally mandated cost of living adjustment (based on CPI; benefit levels cannot be adjusted downward even if CPI trends negative). The legal minimum wage was above the $7.25/hour federal minimum in 31 states in 2022 and 28 of those states will have increases averaging 8.7% in 2023.

Taken altogether, the economic outlook is murky. Though it would be unprecedented to curb the recent high inflation levels without prompting a recession and increasing unemployment meaningfully, the tight labor market could give the Fed a chance to successfully engineer a soft economic landing, allowing consumers, which account for about two-thirds of economic output, to keep spending at reasonable levels while absorbing higher interest costs.

There are other relevant factors to consider, including likely lower fiscal stimulus under split-party control of Congress, the potential for the Russia-Ukraine war to end sooner than expected, and investments to bring production back to the U.S. to lower supply chain risks highlighted by the pandemic. As the one-year anniversary of the war and related energy price spike passes, it is possible that comparisons to a year ago will bring inflation closer to the Fed’s target even without prices resetting to pre-pandemic levels. Whether we enter a technical recession or not, the timing of the Fed’s signaling that it will cease raising interest rates will be a key to propelling the market to new highs.

We will remain vigilant on behalf of our clients as we analyze newly released economic and corporate data throughout the year and strive to achieve attractive risk-adjusted returns. We are committed to our long-term focus and emphasis on high-quality companies with strong balance sheets and prospects that are undervalued by the markets. We again thank all our valued clients for their trust and conclude by wishing everyone a happy, healthy, and wonderful 2023.

~ KCM Portfolio Management Team ~