Q1 2022 – “Despite Economic Headwinds, Positive Indicators Shine Through”

Download newsletter in PDF format

Recent newsletters correctly identified key themes for the markets, but some of the particulars have been unexpected. We highlighted the possibility the equity market could be poised for a break after one of the best three-year performance runs in history, and that inflation and higher interest rates would be critical drivers of market action. Both have indeed ramped up since our last newsletter.

The extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus measures taken to boost the economy amidst the COVID pandemic has increased money supply. Coupled with stubbornly persistent and well-documented supply chain challenges, inflation has increased and production of goods (supply) has been limited relative to demand. These challenges remain, as evidenced by China recently shutting down Shanghai, the 3rd largest city in the world, because of COVID. Russia’s atrocious, larger-than-expected invasion of Ukraine has given rise to heightened economic hurdles and uncertainties. Energy and other commodity prices have risen sharply (from already elevated levels), further fueling inflation fears. Disruption from the war and sanctions on Russia will exacerbate the supply-side inflationary problems worldwide in the near-term, and in more ways than many appreciate.

Russia supplies about one-third of Europe’s natural gas, and its pre-war oil production represented about 7-8% of the roughly 100 million barrel per day worldwide demand for oil. The world cannot immediately replace that supply (or portion of it not getting to market) because it lacks immediately-available capacity, and strategic petroleum reserves are not sufficient for reserve releases to have a durable impact on the world’s supply and demand levels. In addition, Russia controls significant market shares for widely-used methanol-derived chemicals, sapphire substrates and rare-earth elements used to make semiconductors, and fertilizer. Also in agriculture, Russia and Ukraine combined produce 12% of the world’s wheat, 18% of its barley, and accounts for 52% of its sunflower oil exports.

Potential lasting shortages (or withholding for retaliatory purposes) of these critical supplies further threatens to limit production of new supply and/or inflate prices for energy, food, and other goods and services as costs are passed through globally. A ceasefire won’t necessarily mean sanctions are lifted.

Besides the potential for inflation to crowd out discretionary spending, another economic headwind is a much lower level of fiscal stimulus this year, after recent COVID-induced extraordinary spending. Plus, student loan payments will no longer be deferred beginning in August, and tax refunds could be lower than expected this year because child tax credits were paid early. The yield curve is signaling a potential looming recession. In all, there is no shortage of economic headwinds to consider. But there are some positives.

The labor market remains strong, as are consumer balance sheets. And there is still a lot of pent up consumer demand for a range of products and services. In addition, inventory-to-sales ratios remain extremely depressed, suggesting eventual economic strength from replenishment, as supply chain issues are resolved. The consumer has been resilient to date.

Historically, equities have acted as a good hedge on inflation, as companies adjust pricing. Many companies have been generating cash and increasing buybacks, dividends, or both. Despite higher inflation, corporate profits have remained robust, with margins holding up well. S&P 500 component companies had 16.89% operating profit margins collectively last year, the highest level ever. Current forecasts point to further increases for this and next year. We will find out more about sales and margin sustainability as companies release their latest quarterly earnings reports in the coming weeks. We expect near-term headwinds to produce more negative than positive earnings revisions and/or less visibility within updated outlooks. But the damage could be limited as the sell-off during the 1st quarter has discounted some of the expected weakness.

The recent rise in interest rates driven by inflation has drawn many comparisons in the popular press to the 1970’s, the last time inflation readings have been this high. The Fed will raise rates as necessary to combat inflation, but nobody knows how high they will get. The potential for near-term, inflation-induced demand destruction could limit how much the Fed needs to do compared to the economy’s self-correcting mechanisms. Supply and demand imbalances will eventually be restored to the commodity markets leading to more normalized prices, though the timing is uncertain. The Fed will try to manage a soft landing, bringing inflation under control with as little damage to the economy as possible.

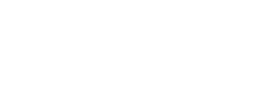

Despite the uncertainty, it is worth noting some of the important structural differences today that could act as a ballast against rising rates longer term. The US economy is much less energy intensive now when measuring energy consumption versus real GDP (Exhibit 1).

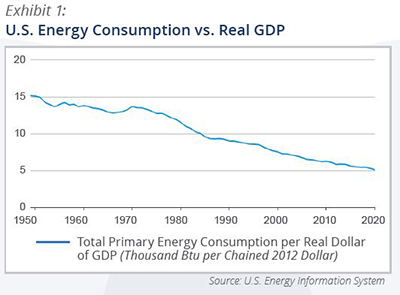

Key drivers of economic growth include the size of the labor force, labor force productivity, and technology employed. One constraint for long-term economic growth, both domestically and worldwide, are the decreasing fertility rates observed in the U.S. and virtually all other economically developed countries. The following Exhibit 2 shows that global fertility rates have come down dramatically. In 2019, the statistically average woman in the world was expected to have 2.4 children, less than half the level of the early 1960’s (the split, thick purple and white sloped line). The dotted lines, from top to bottom, represent low, middle, and high income country aggregates.

Fertility rates are highest in poorer countries, particularly in Africa, the Middle East, and in certain South American countries. The thinner solid lines show the rates for the six highest GDP countries in the world, representing 59% of the world’s GDP and 44% of its population in 2020. The thick, solid, horizontal purple line represents the 2.1 child population replacement rate needed to maintain a population’s size.

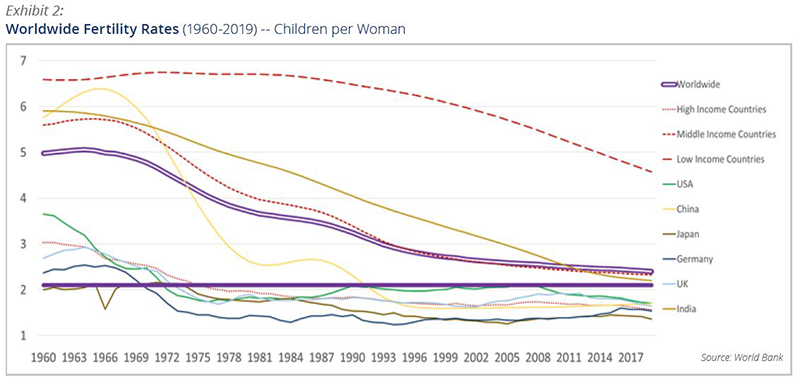

Countries with fertility rates below it will experience an aging demographic and a decrease in population size over time, as is happening in the U.S. (see Exhibit 3). This reduces the supply of labor available to fuel economic growth longer term and increases the ratio of working people to retired-age people; projections call for the oldest Americans to make up an increasing proportion of the U.S. population in the coming decades.

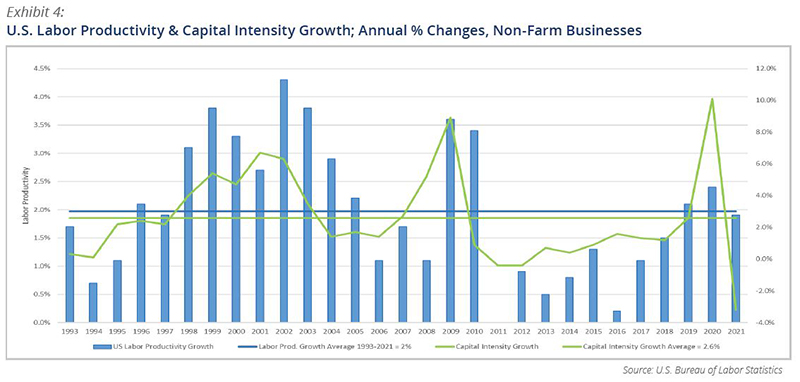

Besides the size of the labor pool, U.S. productivity needs to be considered. Excluding 2009 and 2010, when coming out of the Great Recession, U.S. labor productivity has mostly grown at below long-term averages since 2005. Productivity saw its last big spike during the mid- to late-1990’s through the mid-2000’s, as the proliferation of personal computers and automation drove efficiencies. Their increased use contributed significantly to different components of labor productivity growth. Capital intensity accelerated as companies invested more in technology, allowing for more or higher quality equipment per worker.

Exhibit 4 also reveals a positive relationship between capital intensity and labor productivity growth. Capital intensity has declined significantly since the pandemic, which will inhibit near to medium-term economic growth. In addition, the application of PCs, databases, etc. allow for increases of multifactor productivity growth, which is to say advancements in production techniques and other operational efficiencies resulting from the use of technology (e.g., better connectivity between sales and production teams and related improved inventory management).

A key metric to watch is how the prospect of higher interest rates influences the potential reversion to the mean in capital spending. But with business prospects more clouded, it seems dividends and buybacks might be favored over capital expenditures in the immediate future, which could benefit shareholders more than the broader economy. Significant technology advances could drive productivity higher through further automation or utilization of artificial intelligence. However, displacing labor in service industries is harder because tasks are typically not uniform and predictable, requiring judgment, situational awareness, the ability to read human emotions, understand voice tones, etc.

It is difficult to predict what the market and interest rates will do and market timing is a dubious exercise. An overthrow of Putin would likely trigger a significant rally, for example. Commodity markets may take more or less time to correct. As your money manager, we aim to invest in attractively-valued companies that we believe are better positioned given world and market trends. For our clients, we own financially-strong companies in a variety of industries that do well at different points of economic cycles, thus muting return volatility and often providing better performance when the broad indexes are underperforming. We take this opportunity to again thank our clients as we constantly renew our efforts on their behalf.

~ KCM Portfolio Management Team ~