Q4 2019 – “Ending the Decade with a Strong Finish”

Q4 2019 – “Ending the Decade with a Strong Finish”

What a difference a year makes! A year ago, market watchers were worried about rising interest rates, trade friction (the U.S. – China trade dispute), and geopolitical tensions, which tempered investors’ risk appetites, resulting in a yearly decline for the S&P 500 Index for the first time since 2008 — “The Great Recession”. In 2018, these concerns led to the worst return for the month of December since 1931, and the S&P 500 finished calendar year 2018 down 6%. Fast forward to 2019 and the markets ended with an exclamation point, pressing the S&P 500 to all-time record highs. While the market vacillated between risk-on and risk-off at various times throughout the year, in the end stocks and bonds had an extraordinary run in 2019, posting their biggest simultaneous gains in over two decades. The S&P 500 Index finished 2019 with a YTD gain of 31.49%. We have to go all the way back to 1997 for last time the S&P 500 Index produced a greater return, when it advanced 33.36%.

For the first time in U.S. history, the U.S. economy started and ended an entire decade without a recession. The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) began 2019 forecasting two interest hikes for the year, but ultimately became concerned about the growth trajectory of the U.S. economy, which triggered a pivot in monetary policy as we entered the back half of 2019. When it was over, the central bank ultimately trimmed interest rates three times in the last six months of the year in an attempt to prolong the current economic expansion.

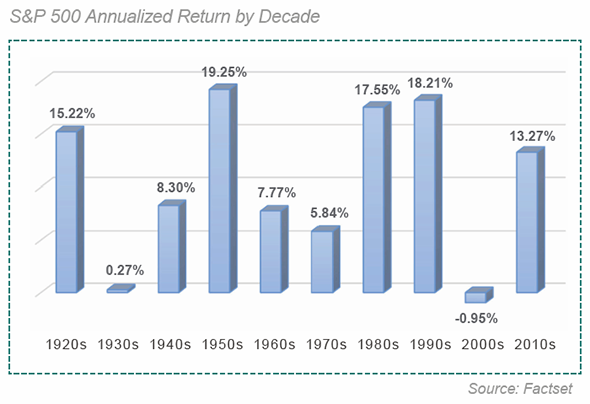

In a historical review of stock market performance by decade, the following chart shows annualized returns of the S&P 500 Index for each 10-year period since 1910. The most recent decade ending December 31, 2019, resulted in a 10-year annualized return of 13.56%, the fifth best in over 100 years. A college graduate of 2020 could reasonably presume that the stock market only goes up considering they were just 11 years old during the last significant stock market decline of -37% in 2008.

On the other hand, those of us that were in the investment industry at that time may recall that 2000-2009 was a painful decade, ending with The Great Recession, and the S&P 500 delivering a 10-year annualized return of -0.95% through 2009. I have often referred to this 10-year period as the “lost decade.” It started out with three years of negative returns (2000 – 2002), with each year progressively worse (more negative) than the last. While we don’t anticipate a repeat of the lost 2000s anytime soon, following the outsized returns of the most recent decade, a review of past poor performance is a healthy reminder that markets don’t always go up, and helps keep risk awareness from fading away.

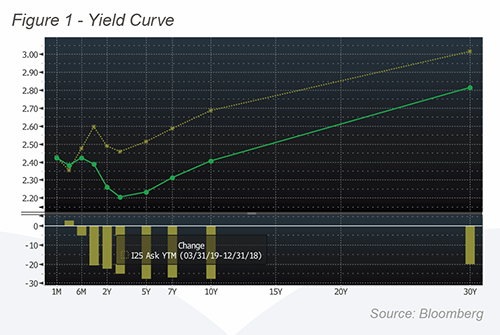

Looking ahead, with the Fed cutting its short-term benchmark interest rate target to a range of 1.5% to 1.75%, the economy should have a stable tailwind from monetary policy throughout 2020. While the Fed signaled a pause in rate cuts during the October meeting, the central bank made it clear that they were not about to start hiking interest rates either, nor were they on a pre-set course for short-term rates moving forward.

On the other end of the yield curve, long-term interest rates in the United States are likely range-bound for the near future between 2.5% to 4.5%. We believe the main driver of monetary policy will continue to be the U.S.-China trade negotiation outcome. Globally, most economists anticipate that the top 23 central banks, which collectively set policy for almost 90% of worldwide economies, will continue to maintain a dovish stance overall (i.e., accommodative, low interest rate policies).

The challenge that global central banks will have, given current low, ultra-low, and even negative interest rates for some, will involve their ability to address potential economic slowdowns through traditional monetary policy maneuvers alone (i.e., rate cuts). Government officials will therefore need to “pick up the baton” in the event of future slowdowns and implement fiscal policies to help strengthen their respective economy, or at least attempt to soften the blow of a recession.

One trend that stood out during the decade was how pervasive “protectionism” has become throughout the world. Most Americans are familiar with U.S. and China trade dispute, but the rest of the world is also grabbing for a piece of preciously scarce growth. In periods of abundant growth, countries tend to be more forgiving of “unfair” practices by which competitors use to gain access to foreign markets. The world is not in that type of environment. The U.S. Corporate Tax Reform of 2017, deregulation, and new trade agreements were all put in place to better position U.S. companies in the global marketplace, in an attempt to capture growth. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), aka NAFTA 2.0, that was passed by Congress in December is another example. The “phase one” trade deal with China was announced mid-December and propelled the market to a relief rally. However, as mentioned previously, we believe contention between the U.S. and China will continue to rear its head in the coming decade and beyond. Entering into a trade deal is fairly easy, but monitoring and holding each trading partner accountable to the terms of the agreement can be quite difficult.

Countries outside of the U.S. and China are also undergoing rising levels of protectionism. With the recent election in the United Kingdom giving Boris Johnson a commanding majority, Britain’s exit from the European Union (Brexit) may soon become a reality. However, “soon” is a relative term since the Brexit process started with a referendum held on June 23, 2016. While European Union Ambassadors agreed to extend Brexit to January 31, 2020, and that is likely the date the U.K. will ultimately “leave” the EU, the U.K. will continue to follow EU rules through December 2020, while negotiators attempt to reach a new free-trade deal between the two sides. Additionally, Spain has recently followed Poland with their own version of Brexit among countries threatening to quit the E.U. in the wake of increasing protectionism.

With that said, as we look to 2020 and beyond, we believe that the equity markets are poised to continue their upward trajectory due to corporate earnings growth and a decent economic backdrop. There may be some bumps in the road, and even major temporary shocks along the way, similar to what we experienced in December 2018, but nonetheless, we anticipate equity markets throughout the world to produce at least modestly-positive returns in 2020.

2020 is a U.S. presidential election year, and the one thing we can forecast with a high degree of certainty is that, after the first week in November, nearly half of the population will be disappointed with whomever is elected. While political rhetoric will heat up throughout the year, it is important to remember that most campaign promises end up empty, and presidential and congressional hopefuls woefully overestimate their power to get things accomplished.

This new world of “low growth” should continue to favor those companies that have been able to capture market share and grow their revenues during the past several years in spite of slow global economic expansion. Therefore, we continue to expect growth investing to outperform value investing for the foreseeable future. Investors need to be aware, however, that the valuation premium for these “growth” companies is relatively high. Any missteps will surely result in significant stock price depreciation, so company selection is critical, and proceeding with caution is prudent. At Kornitzer Capital, we focus on growth companies that are beneficiaries of long-term secular growth trends with the potential to grow regardless of the economic backdrop. We gravitate towards premium companies that have the best competitive positioning within the marketplace and the potential to capture the lion’s share of the growth presented by the trends on which we focus. Onward to the 2020s decade we go!