Q1 2019 – “How the Markets Came Stampeding Back in 2019″

Download newsletter in PDF format

Equity markets produced a significant reversal in the 1st quarter of 2019 following one of the worst periods of performance to close out 2018. Year-to-date through March 31, the S&P 500 Index posted a return of 13.65%, its biggest quarterly gain in nearly a decade. Much of the reversal in market sentiment was a result of the change in the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) policies, providing a more growth-friendly backdrop, combined with the anticipation that a U.S. – China trade deal is imminent.

Regarding monetary policy, recall that in late 2018, Fed officials were targeting between one and three short-term interest rate increases for this year and a continued reduction in the Central Bank’s $4 trillion balance sheet – a wind down of quantitative easing (QE). However, expectations for monetary policy changed in March as the Fed disclosed it is not likely to increase interest rates in 2019 and will stop shrinking its balance sheet by September, extending quantitative easing. This pivot in the Fed’s policy provided a more growth-friendly tailwind for capital markets.

Furthermore, nearly all of the world’s central banks are keeping interest rate increases on hold, a signal to investors that low rates will continue significantly longer than most expected just a year ago. The European Central Bank (ECB) ended its quantitative easing program in December, where it was carrying monthly purchases of $35 billion of government and private debt to keep interest rates low. However, in March, the ECB announced it intends to launch a new QE stimulus program to support the eurozone economy via cheap loans for banks, and hold the key interest rate at -0.4% throughout 2019.

Historically, one way a recession develops is from interest rates being too high, which inhibits the economy’s ability to grow. The Fed’s recent halt to interest rate increases has alleviated this fear, but now the worry has shifted to signs of slowing economic growth in spite of a more dovish Fed. In fact, some market strategists are forecasting the Fed may have to lower short-term interest rates before year-end to stimulate additional growth.

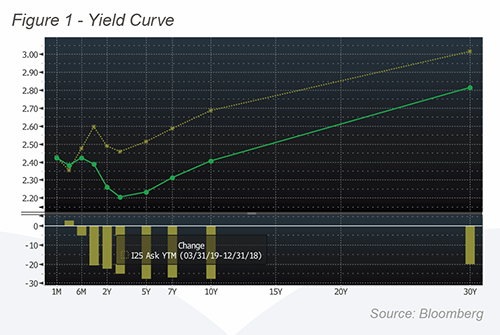

The uncertainty in the trajectory of our economy is reflected in the inverted yield curve (illustrated below). An inverted yield curve occurs when the yield on short-term Treasury bills become higher than the yield on intermediate term bonds, in spite of the term-premium investors usually require for longer maturity bonds of the same credit quality. This unusual phenomenon generally signals falling growth expectations and has preceded every recession in the U.S. since 1975 (except a brief inversion in 1998), although it often takes over a year for this to materialize once the yield curve becomes inverted.

While we do not believe a recession is imminent, the markets are at an inflection point. The Fed’s change in monetary policy is either going to extend the current 10-year economic expansion period or be a signal that the end of the growth cycle is near. A recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of economic contraction (negative economic growth) as measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Since official GDP numbers are typically released two months after the end of a quarter, the economy could be in a recession up to eight months before it’s “officially” announced. Financial markets don’t wait for official recession announcements and stock market drawdowns occur quickly once signs of an economic recession appear. With that said, we believe an extension to the current economic expansion is the more likely outcome for the remainder of the year.

The sustained robustness of the U.S. economy relative to the rest of the world provides some confidence to believe domestic economic expansion will continue. While the U.S. economy is experiencing some deceleration, growth is simply moderating from above trend to in-line. In early March, the Commerce Department reported that the U.S. trade deficit hit a record last year. As imports grew faster than exports, the U.S. economy accelerated throughout 2018 while many of the world’s economies slowed. While some media outlets portrayed this as a dire consequence of ongoing trade disputes, we view the smaller trade deficit goal that President Trump is seeking as unrealistic. As the world’s largest economy, the U.S. is also the largest importer of goods and services, consuming about 14% of total worldwide exports.

The U.S. accounts for nearly 25% of the world’s GDP and is the largest export destination for China, India, and Germany, and the second-largest export destination for Japan. These four major economies are heavily dependent on exports – nearly half of Germany’s GDP comes from exports, therefore a global decline in demand has the potential to affect their financial systems, employment rates, and even internal political dynamics. The U.S., by comparison, is fairly insulated from the global trade economy. Only about 13% of our GDP comes from exports, and nearly half of those goods and services go to our neighbors Canada and Mexico. The U.S., Canada, and Mexico form a stable trading bloc despite the occasional Presidential tweet. Low dependency on exports limits U.S. exposure to foreign business cycles, while export-dependent countries are vulnerable to fluctuations in global demand, especially from the world’s largest economy.

A U.S. recession would decrease demand for goods, and depending on its severity, could have a significant effect on the business cycles of other countries. The greater the dependence on exports, the more destabilizing the effect of an American recession could be. Some of the most vulnerable economies are already facing serious challenges that would be compounded by a decline in exports. China is already in an economic downturn and Germany is showing some signs of a slowdown in manufacturing. The economic implications of Britain’s exit from the European Union are also still uncertain. This is why modest growth in the U.S. has appeared to be so robust when compared to the global economy.

In our last newsletter, we stated that the resolution of trade disputes was a critical factor in the probability of positive market returns for 2019. Thus far, whenever there are indications of a U.S. and China trade deal agreement, the market responds favorably. We believe trade deal negotiations will come to a close within the next six months, but “ending” the trade war appears to mean something quite different to each side.

China would prefer all tariffs be lifted immediately. However, with China’s history of backsliding on negotiated deals, the U.S. will likely demand that current tariffs remain and the lifting of tariffs occur incrementally, as evidence of compliance to the agreement is substantiated. Trade deals are difficult to monitor and enforce, so Washington needs to hold on to at least some leverage to ensure China follows through. While the general market will see the initial advantage of a trade pact, and some sectors like agriculture will have immediate benefits, others may have to wait for fundamental improvements to business through the reduction of current tariffs in the future.

No period of economic growth in U.S. history has lasted longer than 10 years, dating back to before World War II. While economists are apt to point out that we are now reaching that yardstick, with the last recession ending in 2009, we point out that there are other forces impacting the marketplace that have never existed before, specifically ongoing accommodative monetary policies of virtually all of the world’s major central banks. While a U.S. recession is likely to occur at some point, we don’t believe it will be in 2019. While equity investors should enjoy the 1st quarter’s outsized returns, we wouldn’t be surprised to see a pause or even some giveback in stock prices over the next six months. In spite of this outlook, we recommend investors hold firm, as we believe stocks have some runway for growth into 2020.

BREXIT UPDATE

With the failed series of Brexit votes last month, a Brexit resolution remains in flux, as of this newsletter’s publication date. Multiple outcomes are still possible as British Prime Minister Teresa May continues to negotiate a solution. We expect the most likely outcome will be a delay to allow for continued negotiation. Any movement forward on a negotiated Brexit will likely happen over a long transition period, with an estimated completion around 2025.

The economic impact to-date has been relatively modest. Many analysts thought capital planning and economic activity generally, would have slowed substantially, as the uncertainty of Brexit put a damper on spending plans. However, fear mongers have recently been walking back their predictions of eminent doom. Original financial job losses of up to 200,000 were predicted but are now estimated at only 5,000 to 10,000. Financial job losses will be even less than recent estimates given likely “regulatory equivalence” and ability for the UK to be proactive in providing work visas.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney says the economic impact of an abrupt exit will still be substantial, but the UK is much better prepared now, and the impact will be less severe than originally thought.

The EU will also feel the impact. Job losses and economic performance could be worse in aggregate for the EU, but spread amongst many countries. Brexit will impact the UK in larger relative proportion on a per-capita rate.

Most of the recent weakness across the EU is primarily due to trade disputes, a slowdown in China, and the softness in the auto industry. As Brexit negotiations drag on, capital investment plans could continue to be pressured, until flows of goods and services become normalized. An orderly, negotiated Brexit on the other hand might actually induce a boost to economic growth from increased investment and pent-up demand.

A hard, no-deal Brexit, will create the most risk and uncertainty compared to other potential outcomes. However, as BoE Governor Carney recently stated, the UK is much better prepared than when the process began over two years ago.

General risks from a hard Brexit include:

– Economic malaise from job losses and logistical repositioning;

– A seizing up of the global financial system, reduced liquidity or increased volatility;

– Increased inflationary pressures from logistic delays and increased tariffs and taxes;

– Increased regulatory burdens and operating costs as companies may need to duplicate or restructure their regulatory and compliance apparatus to deal with multiple jurisdictions; and

– Continued uncertainty.

In regards to clearing, settlement, and custody within the financial markets, the EU and the UK have agreed to keep existing structures operational for at least 12 months and that existing equivalence rules will continue to apply, with central securities depositories continuing to be fully functional.

The EU and UK support continued access to UK and EU central counter-party clearing, so there should be no disruption to the financial settlement processes now in place. According to the BoE, banks and financial firms in the UK have the capital and liquidity to bear a disorderly, no-deal Brexit, and the European Central Bank and BoE are prepared to provide additional liquidity if necessary.

We continue to monitor the situation, but currently expect any substantial economic disruption caused by a disorderly Brexit to subside within six to nine months as supply chains are reorganized and normalized. The UK was an economic beacon long before it became more entwined with the European Union, and we expect the country to continue to prosper over time.