Q3 2017 – “Interest Rates & the Federal Reserve”

The equity markets continued their upward trajectory during the third quarter, with most market indices closing the quarter at an all-time high, or close to their record highs. This defies the well-known trading adage of “sell in May and go away” that warns investors to sell their equity holdings in May to avoid the typical volatile months of the summer and come back in the Fall. The Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) rose nearly 4% for the quarter, marking its eighth straight quarter of positive gains. The Russell 2000 was up 5.67%, its sixth consecutive positive quarter. It is noteworthy that there have been only five other times since 1980 when the Russell 2000 had positive returns in the first three quarters of the year.

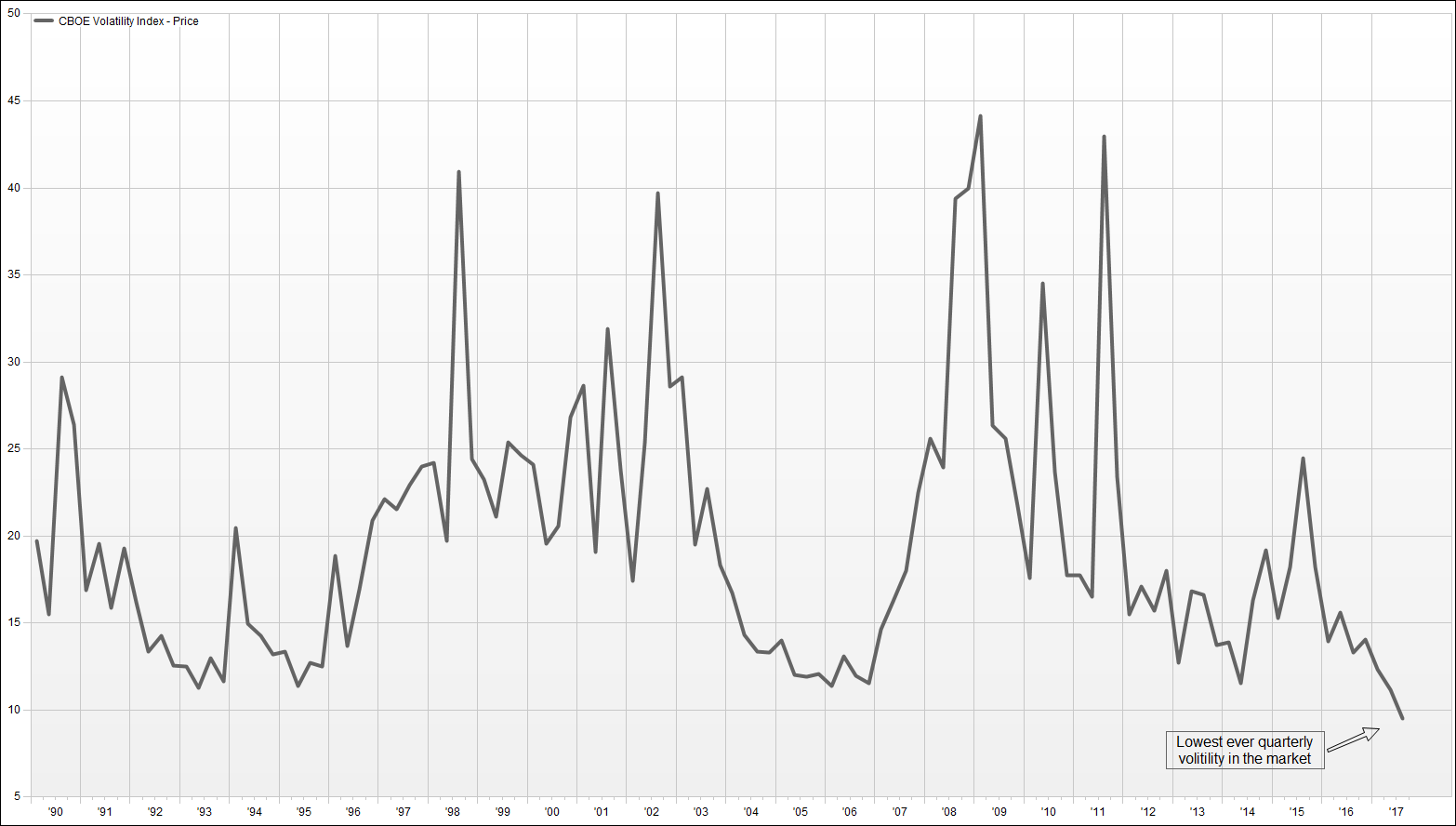

Not only did the markets continue upward but it was also the least volatile third quarter as measured by the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) for the past 20 years and was the lowest volatile quarter since fourth quarter of 2006 (see chart below). Emerging market stocks had a strong quarter and are on pace for their best year since 2009. While the Federal Reserve (The Fed) has raised their benchmark lending rate two times this year so far, with another increase expected in December (for a total increase of 75 basis points for the year), the rise in short term interest rates had minimal impact on long term rates, with the 10-year treasuries trading in a narrow range of 2.20 – 2.40% for much of the year, as signs of inflation continue to remain elusive.

Chart: Average Quarterly CBOE Volatility Index

Chart source: Factset

In a recent speech, Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen defended the central bank’s projection for a gradual path of rate increases over the next few years despite the past few months of unexpectedly low inflation, which under the Fed’s preferred measure has undershot the central bank’s 2% target for much of the past five years. Although Chairwoman Yellen said she expects inflation to gradually move up to the target, she acknowledged the uncertainty surrounding that prediction and some members on the central bank committee disagree. Some policy makers are starting to be of the opinion that weaker inflation reflects structural changes in the economy rather than a temporary phenomenon. The sole opposing vote of the central bank’s two rate increases this year has been the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari.

Mr. Kashkari was closely involved in damping the initial stages of the financial crisis in early 2008 by working closely with then Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson and eventually being appointed to lead the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the initial Federal asset buying program to purchase $700 billion of the outstanding mortgages held by financial institutions. He believes that the raising of short term rates should be delayed until the inflation rate actually hits the 2% level on a 12-month basis.

Income reliant investors continue to be hopeful that interest rates will rise. Yields did soar into the end of 2016, as investors anticipated that President Trump’s pro-growth agenda would drive inflation and economic growth higher, giving the Fed a foundation on returning to a more “normalized” interest-rate environment, but since then there has been minimal movement of interest rates. The Fed has raised rates four times since 2015 and has penciled in one more rate increase this year (likely December) and three increases in 2018.

Why is it taking so long for interest rates to increase? From a monetary policy perspective, moving too quickly could slow growth unnecessarily, but raising rates too gradually could create an inflationary problem down the road that might be difficult to overcome without triggering a recession. Additional global forces are impacting the market. While the U.S. central bank is discussing returning to “normalized” levels, the rest of the world’s central banks continue to buy assets, and investors continue to seek yield throughout the world, and U.S. yields continue to be attractive worldwide.

During the September Fed meeting, policy makers dropped their average prediction for long-run interest rates from 3% to 2.8%. The long-run neutral rate of interest, the natural rate, has a big influence on how policy makers set rates. It is the rate that should keep inflation steady when the economy is running at full capacity and is key to judging monetary policy. The further rates are below it, the more they boost the economy. And once they reach it, monetary stimulus has been fully withdrawn. Recall that the fed funds rate was 5.25% in August 2007, significantly higher than today’s 1% to 1.25% range. In this environment, equities should continue to benefit into the foreseeable future, but there is another force that should be a positive driver of equities and the economy: the potential of tax reform.

Given Congress’ inability to pass legislation this year, the hit rate of proposed legislation becoming law this year does not inspire confidence, but there is time for Congress to deliver on the Republican promise of a simpler tax code with lower rates, but time is vanishing to accomplish it in 2017. The 1981 tax cut laid the foundation for a quarter-century of strong, noninflationary growth, which, despite three subsequent recessions, averaged 3.4%. The framework of the proposed tax reform would lower taxes on corporate profits, give incentives for business investment, and fewer and lower individual income tax brackets and the end of estate taxes. Under the Republican’s plan, the corporate tax rate would fall to 20% from 35% and the top rate on individuals could drop to 35% from 39.6%. As with any proposal in a divided congress, what is proposed and what actually becomes law will be vastly different.

A significant stumbling block for the proposed tax reform would be that it eliminates state and local tax deductions, placing high tax states’ citizens at a disadvantage. The elimination of the deduction was to help pay for the tax cuts by generating $1 trillion over the next 10 years. While it comes as a surprise, this isn’t the first time that the elimination of the deduction has been proposed. It was proposed in 1986, the last time that Congress revamped the tax code and failed to gain support from high-taxed states. But if it is removed, there will have to be changes elsewhere to help offset the corporate tax cut.

The most important news is that the plan would make U.S. businesses more competitive around the globe. The corporate rate, which is currently 35% and the highest in the developed world, would fall to 20%. While short of candidate Trump’s campaign platform of a corporate tax rate of 15%, it is below the industrialized world’s 22.5% average. This will be the first significant fiscal policy that could provide a tailwind to the equities market and the economy since the start of the financial crisis and importantly offset the increase in rising interest rates and the steps that the Fed is taking to reduce its balance sheet.

There are two key events that will take place over the coming year that will likely have an impact on the market. The first is that the Fed will begin to shrink its $4.5 trillion bond portfolio in October in an effort to bring it into alignment with levels prior to the financial crisis. The Fed’s balance sheet was less than $1 trillion before the 2008 financial panic. The central bank will be pulling $10 billion a month from the financial system and increasing that amount gradually over time. In a year, the anticipated monthly amount will be up to $50 billion, a level that is more than the Fed bought each month during the first phase of QE3 in 2013.

The three quantitative easing programs injected capital into the economy and kept rates low, while increasing the central bank’s balance sheet. Conversely, when the central bank sells or redeems those securities, the cash it receives is withdrawn from the economy, and in theory increases rates. We believe the attractiveness of U.S. yields relative to global alternatives will help support lower yields initially. But if multiple central banks throughout the world embark on drawing down their balance sheet in the same manner as the U.S., interest rates could be pressured to go higher. Nonetheless, currently the U.S. is the only central bank with a tightening policy.

It is debatable to quantify succinctly the impact of the QE programs to the economy over the past decade. After spending $2 trillion on government bonds in an effort to stimulate the economy, there is still uncertainty on how, or even if, it worked. Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen has admitted that quantitative easing is still poorly understood even by the experts. Therefore, this monetary experiment is far from over and will likely continue to play out over the next several decades, not only in the U.S., but also in the world.

The second item facing the Fed is the potential for a leadership shake-up next year. Chairwoman Yellen closes in on the final months of her four-year term as the leader of the U.S. central bank and while she is a top contender for another term as Fed chair, President Trump has voiced that there are additional candidates that he is considering. Chairwoman Yellen has been very transparent with the market on the pace of rate increases and deleveraging of the central bank’s balance sheet, and any change in the committee makeup, particularly with the Chair position could have an impact on the policies currently expected by investors.

Inevitably, there will be geopolitical issues impacting the market, such as North Korea and Spain, but we believe they are transient to the marketplace. Not to downplay the seriousness of those events, because as the news flow ebbs to and fro, it will have an impact to the market. We just do not believe they will have a lasting impact to the U.S. economy and market.

So far, the current economic expansion has lasted 101 months (beginning in June 2009). The National Bureau of Economic Research shows only two U.S. expansions that lasted longer than this one. The great expansion of the 1960s went on for 106 months and a 120 month expansion that went from 1991 to 2001. To top that longest expansion, the current recovery would have to continue growing past June 2019. The most common cause of U.S. recessions in the postwar era has been monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve as a means to fight inflation, an issue that is non-existent today.

Historically, the fourth quarter is the strongest return quarter of the year and has a positive return nearly 75% of the time since 1980. With the underlying momentum driving the U.S. economy, the equity market should continue to perform well for the rest of the year. We continue to find value in the marketplace and would advise clients to continue to take advantage of any market pullback to put additional capital to work.