Q2 2016 – “Is The Demise of Globalization Near?”

The status of globalization took center stage this past quarter with the United Kingdom’s June referendum (Brexit) to leave the European Union. It was the highest turnout in a UK-wide election since 1992 and fairly evenly divided, as the “leave” camp won by a 52% versus 48% margin. Stock markets dropped world-wide the day after the results but had subsequently recovered most of the initial losses within the week following the vote.

There is no certainty in how the UK and the EU will proceed with the separation process. As of the printing of this newsletter, the UK has not yet invoked Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which is necessary to begin negotiations of its separation from the EU. While this is the first time a nation has opted out of the EU, in 1982 Greenland, one of Denmark’s overseas territories, voted to leave the EU (ironically at similar margins to the UK vote). It took nearly three years to negotiate its exit deal. Obviously the UK’s integration into the EU’s economy is more significant than Greenland was at that time, so there is a high probability that this will be in the headlines for years to come. The most immediate impact has been the sinking of the British Pound to a 31 year low. The day of the referendum, it took 1.5 dollars to buy one British pound, and on July 5, 2016 the conversion ratio was 1.3, a level it hasn’t seen since 1985.

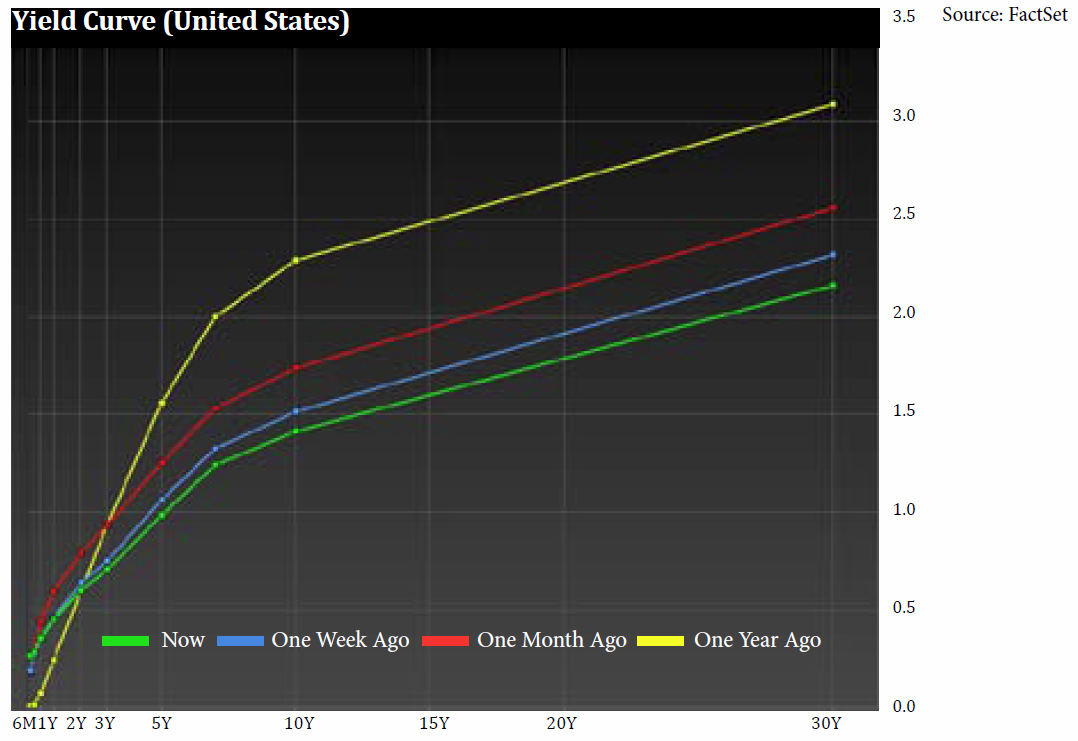

The turmoil that Brexit will have on the European economy has impacted interest rates in the US, as investors seeking relatively safe interest-bearing securities have driven interest rates lower (see Chart 1). In the first part of July, the U.S. 10-year Treasury Note yielded 1.367%, a yield not seen since the 1940’s. At the June Fed meeting, Janet Yellen, Chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, gave a cautious outlook for rates after the May monthly employment numbers reflected loss of momentum in the labor markets. The Fed also lowered projections for how much it will raise rates in the years ahead, and this was before the results of the Brexit vote were known. As of July, this is the longest period in 40 years between the first rate hike and the second, with nearly seven months transpiring since the first rate hike in a decade last December. The Fed will continue to be data dependent, but unless things change materially for the better in the coming months, the Fed will likely keep its rate policy unchanged for the rest of this year. The impact to the United States in a post-Brexit world should have minimal economic impact. Exports make up less than 14% of U.S. GDP, according to the World Bank, and the UK accounted for just under 3% of total revenues for the companies in the S&P 500 last year.

Potentially the concerns of the negative perceptions that globalization has had on economies by the Brexit vote could have an impact on businesses throughout the world. But even after the Brexit vote outcome, key leaders of the “leave” campaign were very clear in stating that they would like to continue the current economic relationship with Europe, just not so on the regulatory and immigration policies. In a world where growth continues to be elusive, eliminating access to end market for your products seems irrational self-inflecting pain. Nonetheless, during periods of low growth, the discussion around protectionism and nationalism tends to flourish as politicians seek ways to explain the lackluster growth. Even in the United States, trade is becoming a heated topic as the November election nears. We will leave the debate of the merits of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) to the rhetoric of the politicians, the media, and pundits to sway the masses, but in reality, there are more powerful forces driving the change in globalization than the polling booth. With the importance of globalization to U.S. companies and the likelihood that it will remain in the forefront of the headlines for months now, it is beneficial to understand what drove globalization, what companies are saying about it, and most importantly, what it means to you as an investor.

Looking back on history, there are numerous advancements that could be considered as stair-step improvements in the globalization of goods, but none have been more impactful than an idea conceived in the mind of a 24-year-old truck driver, Malcom McLean, in 1937. While he waited hours to unload his delivery of cotton bales at the shipyard, he observed the inefficiencies of the process of unloading each trailer of its cargo and lifting each non-standardized crate into the hull of the vessel. His idea was to develop a system where he could drive his trailer up to the vessel, have the trailer detached from its chassis, lifted onto the vessel, and depart to pick up his next paying customer’s load.

It took McLean nearly 20 years to bring this idea to fruition, but the primary driver to build his first container ship was increased regulation. States were starting to levy fees and weight restrictions that were costing his business. Travelling by water would eliminate those fees and be more cost competitive than trucking alone. He sold his trucking business and entered the shipping business with his first vessel, Ideal X, which was capable of carrying 58 containers. At the time of its first voyage, hand-loading a ship cost $5.86 a ton. Using his specially designed, standardized 20 ft. containers only cost 16 cents a ton. Thus, the globalization of materials, parts, and labor began to grow rapidly, and today, nearly 90% of commerce ships by sea on vessels capable of carrying over 19,000 containers. Companies are no longer confined to their local geographical reach for labor and end markets, but can access the world. Not only have companies based in the U.S. benefited by offshoring manufacturing to low cost regions, consumers have been able to benefit through lower prices. Additionally, globalization has helped develop emerging economies by enriching its citizens that are now transitioning from providing for their basic needs to having the ability to purchase more discretionary items.

Nonetheless, several years ago globalization started to take a new dynamic. The global labor cost differential started to tighten, and the cost advantage that certain emerging economies had in the 1990’s and 2000’s began to disappear. Specifically in China, companies have disclosed that some Chinese employees were being paid the equivalent, if not more, than their colleagues based in developed economies. As discussed in our first quarter’s newsletter, China realizes that they are losing their low labor cost edge and is aggressively investing in automation to remain competitive. In May, China’s Midea launched a bid to acquire German robotics specialist Kuka AG to further advance that goal. The key for emerging and developing economies to benefit from globalization is to maintain that labor cost advantage, but in an age of automation and robotics, the regions that are able to incorporate technology on the manufacturing floor will be the winner going forward. A recent tour of Ford’s Claycomo, Missouri, assembly plant that produces the Ford F-150 and Ford Transit models highlighted the importance of automation on the assembly floor. For the past decade, robots have replaced a majority of the high costing labor jobs, and technology has eliminated the need for highcost trade specific labor, such as welders, from the assembly line. There is no welding done on the F-150, all of the body panels are connected with adhesive and rivets. Much of the human interaction on the assembly line is towards the final assembly, which tends to be lower costing jobs. Technology and automation will continue to change the labor costs mix in the manufacturing process.

With the digitalization of the economy through robotics and automation in the manufacturing process, the location of manufacturing is changing. Once the labor cost differential is eliminated by incorporating technology into the manufacturing process, companies start to incorporate other factors into the decision process on where to locate manufacturing to address end markets efficiently. Factors such as tariffs, fees, and local labor laws and regulations start to have less influence on the locale when automation is taking over the work. As a developing economy ages, the natural tendency is for the local governments to increase regulatory oversight, which also tends to increase the cost of operating within that jurisdiction. According to the World Bank Group, over 70% of regulatory reforms recorded in 2015 were carried out by developing countries.

U.S. companies are increasingly putting emphasis on “speed-to-shelf” and “speed-to-market” and some are moving manufacturing to Mexico from China. But this also works in the opposite direction, as developing economies become consumers, companies are “exporting” smaller manufacturing facilities to serve local markets, versus large footprint facilities serving world markets. Globalization is not going away, but is changing, as one would expect that businesses are always seeking opportunities to provide a service or product to their end markets more efficiently and cost competitively. Presently there has never been a cheaper time to transport goods from across the world, given the overinvestment by shipping companies and excess shipping capacity. Nonetheless, the environment is one where often the origin and destination charges to take the container on and off the vessel are more than the cost to transport the container on the open sea.

The nearshoring trend is not confined to only U.S. companies. Throughout the world more and more companies are using nearshoring to reduce operating costs, and with the U.S. being the largest economy in the world, it will stand to benefit from this growing trend. The same drivers that influenced McLean to come up with his Container ship are driving the considerations to regionalize manufacturing, and regardless of the alarmist tone of anti-globalization headlines, businesses have already started to adjust to this new environment through the benefit of advancements in technology.

Where does all of this change in globalization leave the U.S. investors? The U.S. markets will continue to be a safe haven for world-wide investors. The economy in Europe was already on fragile ground before the referendum and will likely be lackluster for the foreseeable future, regardless of the European Central Bank stimulus programs. As investors continue to seek out income options, yields will continue to be pressured lower for longer. With yields collapsing in the rest of the world, the U.S. bond market is one of the few places investors are flocking for yields, pushing U.S. corporate yields lower. We still caution investors that are tempted to reach out on the risk spectrum to capture greater yield and rather continue to be focused on quality high-yield bonds with attractive yields. Dividend paying stocks continue to be attractive, particularly with the increase in volatility giving investors good opportunities to secure relatively attractive dividend yields in quality companies. Relative to the U.S. Treasury 10-year Note, currently there are 318 companies in the S&P 500 now paying a higher yield. We continue to target common stocks with dividend yields of 3 – 4% in companies that have intentions to continue to raise their dividends over time. Don’t be fooled into running for the exit doors when the news blares for new calls for tariffs or protectionism. Companies have already been adapting to a new globalization environment, and out of new challenges, just as McLean demonstrated, are new opportunities.